I want to make a brief case for why we ought to keep the November 20 class focused on infrastructure and materiality, and I want to do it through the video game trope of mirror alignment puzzles. (Apologies in advance if this is a little too “did you know Shakespeare … [turns hat backwards] … was a rapper?!”)

Mirror alignment puzzles start with a source of light that somehow needs to get from here (a crack in the roof) to there (a “sunlight keyhole”). Your job is to position a dozen or so abandoned cave mirrors into a mediating system that takes the light where it wants to go. It’s how you move forward, or access important tools.

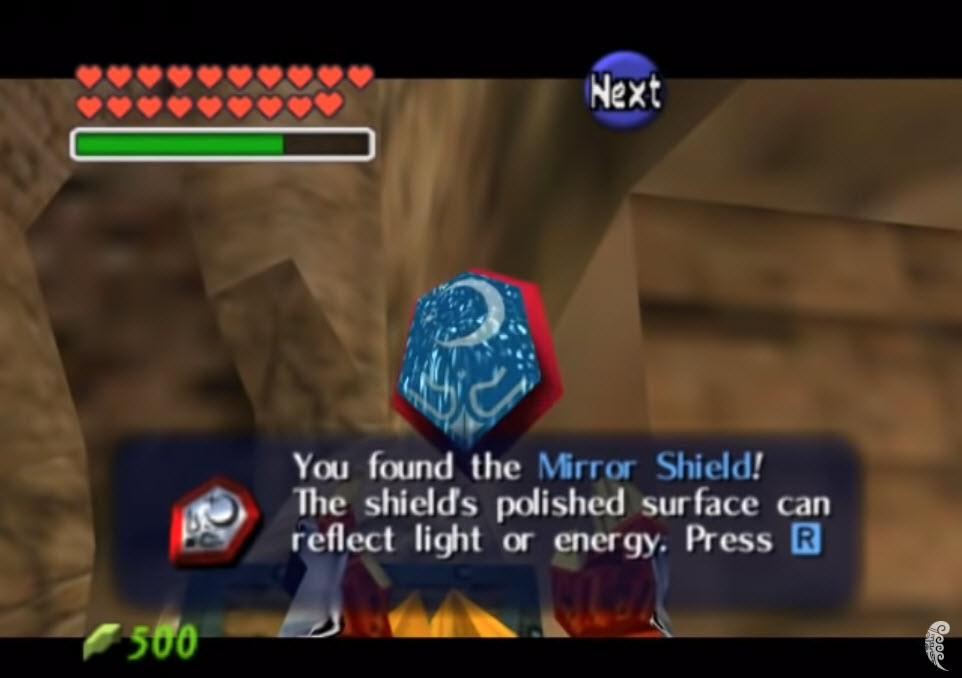

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time

When Jonathan Rauch talks about how the creation of knowledge, he describes it as a “professionalized and structured affair,” a network of “norms and institutions [assembled into] a system of rules for identifying truth.” That there even is a system that checks, balances, reviews, replicates, cites, and confirms its hypotheses is what fundamentally separates the “shared facts” of scholarly knowledge from the irreverent disinformation of “troll epistemology.” (As my other recent post indicates: I’m a bit preoccupied with the blurry boundary between scholarship and conspiracy right now.)

Similarly, when Kathleen Fitzpatrick thinks about “the university of the future” in Planned Obsolescence, she does so by spending a great deal of time reimagining the scholarly author, the monograph, peer review, the university press, and the library not just as discrete mirrors but more importantly as a necessary network for the mission-driven creation and sharing of knowledge.

And since, as Eli Lehrer reminds us, infrastructure is a public good, using a liberal version of the transitive property, we can easily make the case that if infrastructure helps us constitute knowledge and infrastructure is a public good, then it must be that the constitution of knowledge is a public good. Knowledge is good! This may sound like nothing new–it’s basically something we knew already–but it’s true (here) only if each of the initial premises is true. And if we had to work backward from our conclusion, what could we really say about these initial premises? How convincingly can we argue that infrastructure is (or can be) a public good, or that infrastructure helps us constitute knowledge? Could we get into the weeds on these issues with those who are skeptical? (After all, one of the largest partisan gaps in institutional confidence involves higher education.) Can we say anything about the infrastructure of and around DH? Can we speak to the material changes needed to solve the “Grand Challenges” of our time with the same dexterity as we can the ideological changes needed? Is the fact that we are open to substituting this material indicative of a potential blind spot?

Or, to cannibalize a line of thinking from Renaissance scholar and editorial theorist Gary Taylor: how can you love knowledge if you don’t know it? How can you know it if you can’t get near it? How can you get near it without its underlying infrastructure?

Rather than looking in the mirror to analyze a little more carefully the DH knowledge and experiences we bring to it–what we’ve already read; projects we’ve already started working on–I think we ought to spend a little time looking at the mirrors of DH themselves: the way they are currently positioned; their various misalignments; where the light is and wants to go and how an improved infrastructure can facilitate that process.

And it’s not just the hardware or software either, the mirrors that stand apart from us. I think we ought to consider human infrastructure too: how student or adjunct labor fits in to DH; who or what the public (or their data) is; how our physical bodies are exposed or made vulnerable in DH work.

The materiality of digital infrastructure.

The materiality of human infrastructure.

We’ll need to think too about the ecological systems in which our digital infrastructure operates: the permanence or disposability of machines; energy usage for the creation and preservation of projects; the physical space DH centers and server warehouses and shared repositories require; the carbon footprint involved in our conference travel to present on the shiny new thing.

Shine your mirror shield here long enough…

…and you will receive access, but will irremediably destroy the face.

There’s a lot to talk about, and Matt and Steve bring a lot to the table in this regard through their CUNY and other affiliations. It’s worth spending two hours thinking about.

The video game mirror alignment is a fun angle.

Seconded. I would also like to keep Infrastructure and Materiality for Nov. 20th.

I am fine with either sticking to the syllabus “as is” for Nov. 20 class or changing up the readings.

I do think we should also add the very interesting reading you proposed as a suggested reading for that day, Carolyn!

Thanks, Hannah, I’m glad you find the reading I proposed of interest. It’s a worthy synopsis-style resource that contextualizes and describes the foundations of the significant schools of thought that pre-date DH and, I would add, helps put a wide-angle lens on the emergence of DH.

Michael, upon reflection, I think you really shine light on the importance of infrastructure with the prismatic approach of your post. Especially enlightening is your inclusion of human bodies in the infrastructure spectrum — often left as a glaring opacity in others’ considerations of the subject, through which their normative expositions refract. I’m positively beaming!

Puns aside. I’m in agreement with Michael here. Infrastructure and Materiality feel like crucial puzzle pieces (okay, can’t put aside the puns). I still would love to hear the suggestions that others have. There’s no reason we have to stop discussing material after the light goes out on this class. (ugh)

This fine wordplay reflects well on you, Rob. All in good pun, I say!