I’ve been fairly excited to utilize Voyant to do some textual analysis. I wanted to choose text to analyze that would engage with structural political issues to draw attention to inequalities within our societal structures. Thus, I’m particularly interested in engaging in discussions surrounding systems of power and privilege in modern America. This is why I’ve chosen to do a text analysis comparing and contrasting Brett Kavanaugh’s opening statement for the Senate Judiciary Committee with Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s opening statement.

Before going any further, I would like to issue a trigger warning for topics of sexual violence and assault. I recognize that these past few weeks have been difficult and overwhelming for some (myself included), and I would like to be transparent as I move forward with my analysis on topics that may come up.

My previous research has centered around topics of feminist theory, and rape culture, so the recent events regarding Supreme Court Justice Nominee, Judge Brett Kavanaugh, have been particularly significant to my past work and personal interests.

To provide some very brief context on current events, Kavanaugh was recently nominated by President Donald Trump on July 9, 2018 to replace retiring Associate Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy. When it became known that Kavanaugh would most likely become the nominee, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford came forward with allegations that Kavanaugh had sexually assaulted her in the 1980’s while she was in high school. In addition to Dr. Ford’s allegations, two other women came forward with allegations of sexual assault against Kavanaugh as well. To read a full timeline of the events that occurred (and continue to occur) surrounding Kavanaugh’s appointment, I suggest checking out the current New York Times politics section or Buzzfeed’s news tab regarding the Brett Kavanaugh vote.

The Senate Judiciary Committee surrounding Kavanaugh’s potential appointment invited both Kavanaugh and Ford to provide testimony about the allegation on September 24, 2018. Both Ford and Kavanaugh agreed to testify. Ford and Kavanaugh both gave a prepared speech ((initial testimony) on September 24, 2018 and then were asked questions from the committee. For this project, I am only comparing each opening statement–not the questions asked and answers given after the statements were provided. In the future, I believe much could be learned from a full and more thorough analysis including both the statements and the questions/responses given, however for the breadth of this current research and assignment I am only very briefly looking at both individuals opening statements.

This research is primarily exploratory in that I have no concrete hypothesis on what I will find. More-so, I am interested in engaging with each text to see if there are any conclusions that can be drawn from the language. Specifically, do either of the texts have implications regarding structurally oppressive systems of patriarchy and rape culture? Can the language of each speech tell us something about the ways in which sexual assault accusations are handled in the United States by the ways an accuser and the accused present themselves via issued statements? While this is only one example, I would be curious to see what type of questions can be raised from the text.

To begin, I googled both “Kavanaugh Opening Statement” and “Ford Opening Statement” to obtain the text for the analysis.

Here is the link I utilized to access Brett Kavanaugh’s opening statement.

Here is the link I utilized to access Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s opening statement.

Next, I utilized Voyant, the open source web-based application for performing text analysis.

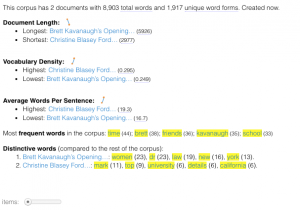

Here are my findings from Voyant

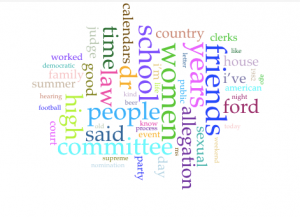

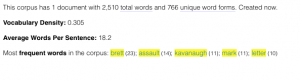

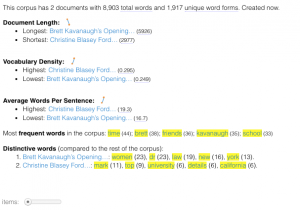

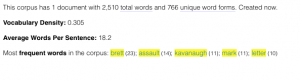

Kavanaugh’s Opening Statement:

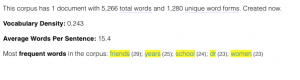

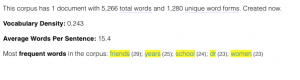

Ford’s Opening Statement:

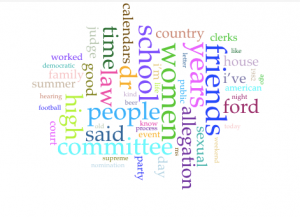

Comparison (Instead of directly copying and pasting the text in as I had done separately above, I simply inputed both links to the text into Voyant)

There are several questions that can be raised from this data. In fact, an entire essay could be written on a variety of discussions and arguments that compare and contrast the text and further look at how they compare with other cases like this one; however for the breadth of this short post I will only pull together a few key points that I noted, centering how the text potentially relates to the structural oppression of women in the United States.

First, I thought it was interesting that Kavanaugh’s opening statement was significantly longer (5,266 total words) than Ford’s (2,510 total words). Within a patriarchal society, women are traditionally taught (both directly and indirectly) to take up less space (physically and metaphorically), so I wondered if this could be relevant when considering the fact that Ford’s opening statement was significantly shorter than Kavanaugh’s. Does the internalized oppression of sexism in female-identified individuals contribute to the length of women’s responses to sexual violence–i.e. do women who experience sexual violence take up less space (potentially without even noticing or directly trying to) in regard to their statements than the accused (in this case men)? Perhaps a larger sample of research comparing both accuser’s and the accused sexual assault statements (specifically when the accuser is female and the accused is male) could provide more insight on this.

Additionally, another observation I had while comparing and contrasting the texts with one another was the most used words within each text. Specifically, one of the most used words in Kavanaugh’s (the accused) speech was “women” which I found to be interesting. Do other people (specifically men) who are accused of sexual violence often use the word “women” in statements regarding sexual violence? Is this repetitive use of the word used to somehow prove that an individual would not harm women (even when they are being accused of just that)? It makes me consider an aspect of rape culture that is often seen when dealing with sexual violence–the justification that one could ultimately not commit crimes of sexual violence because they are a “good man” who has many healthy relationships (friendships or romantic) with women. There is no evidence that just because a man has some positive relationships with women that he is less likely to commit sexual assault; however there is data that states that people are more likely to be sexually assaulted by someone they know (RAINN). I would be curious to look into this further by utilizing tools like Voyant to consider the most used words in other statements from accused people of sexual violence.

Ultimately, this was a brief and interesting exercise in investigation and exploration. I think that there could be many different interesting and important research opportunities utilizing tools like Voyant that look at statements provided by sexual violence survivors and those who are accused of sexual violence. This was just a starting point and by no means is the necessary and extensive research that most done on this topic, rather it remains the beginning for further questions to be asked and analyzed. I’m eager to dive into more in-depth research on these topics in the future, possibly using Voyant or other text-mining web-based applications.