Hannah’s already provided some use cases that I hope help to illustrate why we think that Project T.R.I.K.E will be useful, and to whom. I wanted to backtrack and give some context. Although, as Hannah’s post suggests, it’s quite difficult to suggest a specific starting point for our thought processes, which have developed iteratively until we’re not sure whether we’re trapped in a time loop or not. However, I think I can trace through some of the things I think are important about it.

We really wanted to do something that would be useful for pedagogy. Again, if you want to know how it’s useful for pedagogy, please see Hannah’s post! But we were specifically interested in a resource that would teach methodology, because all of us were methodological beginners who really felt the need for more tools and resources that would help us to develop in that respect. During our environmental scan, we were impressed by the efforts of the DH community to produce a number of useful guides to tools, methodologies, and processes (in particular, please see Alan Liu’s DH Toy Chest and devdh.org), although none of them were doing exactly what we want to do. There are plenty of dead resources out there, too, and we should take that as a warning.

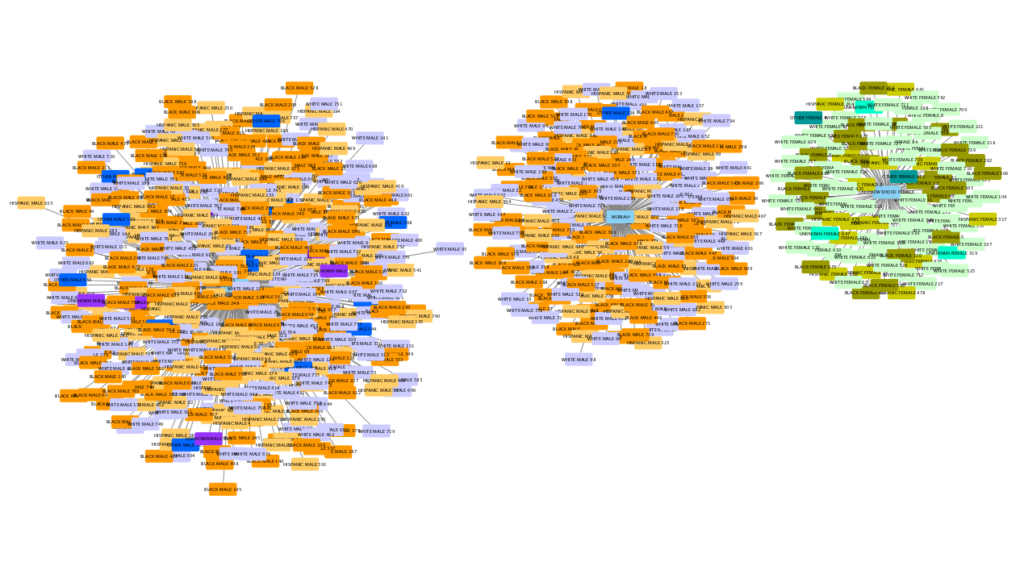

We really wanted to take a critical stance on data by creating something that would highlight its contingent, contextual, constructed nature, acknowledging that datasets are selected and prepared by human researchers, and that the questions one can ask are inextricably connected to the process through which the dataset is constituted. Our emphasis on a critical approach does not originate in this class; I believe all of us had been exposed to theories about constructedness before this. What’s curious about our process is that we went out seeking datasets and tutorials with this in mind, thinking about what we hoped to do, and this conversation ranged far from the class readings, focusing on our own work and also Rawson and Muñoz’s “Against Cleaning” but eventually brought us back to Posner, Bode, and Drucker. None of them, however, came away with exactly the solution we did; we decided that the constructed nature of data is best represented by making transparent the process of construction itself! Project T.R.I.K.E. will provide snapshots of the data at different stages in the process, highlighting the decisions made by researchers and interrogating how these decisions are embodied in the data.

Finally, we really wanted to ensure that we could produce something that could be open to the community. Again, a lot of work in the DH community is openly available, but we also came across some datasets behind paywalls. One repository aggregating these datasets not only made it difficult to access the databases but also had a series of stern lectures about copyright, occupying much the same space on their website that instruction in methodology would occupy on ours! While it is true that some humanities data may invoke copyright in a way that other kinds of data usually don’t, we’d much rather host datasets that we can make available to a wide variety of users with a wide variety of use cases. Limiting access to data limits research.

Think carefully, though. As part of the environmental scan, we came across an article that argues, on the basis of a report partially sponsored by Elsevier, that researchers seldom make their data available, even when they are required to do so. While I expect this is true, I am also suspicious of claims like this when they are made by major publishers, because their next step will probably be to offer a proprietary solution which will give them yet more control over the scholarly communication ecosystem. In a context in which major publishers are buying up repositories, contacting faculty directly, and co-opting the language of open access as they do so, I’d argue that it’s more and more important for academics to build out their (our) own infrastructure. Project T.R.I.K.E. has slightly humbler ambitious, for time being, but it’s an opportunity for us to begin building some infrastructure of our own.

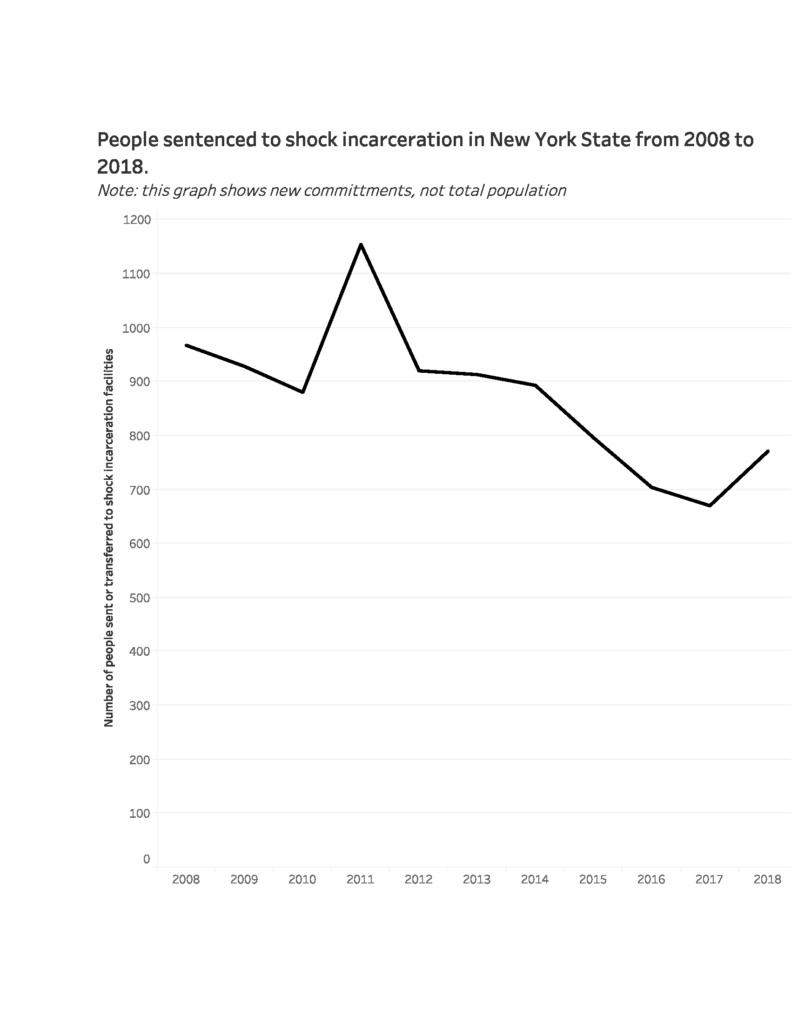

Phew, that’s all for now. See it on Tableau, there’s no comparison.

Phew, that’s all for now. See it on Tableau, there’s no comparison.