To tell the truth, I’ve been playing with Voyant a lot, trying to figure out what the most interesting thing is that I could do with it! Tenen could critique my analysis on the grounds that it’s definitely doing some things I don’t fully understand; Underwood would probably quibble with my construction of a corpus and my method of selecting words to consider. Multiple authors could very reasonably take issue with the lack of political engagement in my choice. However, if the purpose here is to get my feet wet, I think it’s a good idea to start with a very familiar subject matter, and in my case, that means board games.

Risk Legacy was published in 2011. This game reimagined the classic Risk as a series of scenarios, played by the same group, in which players would make changes to the board between (or during!) scenarios. Several years later,* the popularity and prevalence of legacy-style, campaign-style, and scenario-based board games has skyrocketed. Two such games, Gloomhaven and Pandemic Legacy, are the top two games on BoardGameGeek as of this writing.

I was interested in learning more about the reception of this type of game in the board gaming community. The most obvious source for such information is BoardGameGeek (BGG). I could have looked at detailed reviews, but since I preferred to look at reactions from a broader section of the community, I chose to look at the comments for each game. BGG allows users to rate games and comment on them, and since all the games I had in mind were quite popular, there was ample data for each. Additionally, BGG has an API that made extracting this data relatively easy.**

As I was only able to download the most recent 100 comments for each game, this is where I started. I listed all the games of this style that I could think of, created a file for each set of comments, and loaded them into Voyant. Note that I personally have only played five of these nine games. The games in question are:

- The 7th Continent, a cooperative exploration game

- Charterstone, a worker-placement strategy game

- Gloomhaven, a cooperative dungeon crawl

- Star Wars: Imperial Assault, a game based on the second edition of the older dungeon crawl, Descent, but with a Star Wars theme. It’s cooperative, but with the equivalent of a dungeon master.

- Near and Far, a strategy game with “adventures” which involve reading paragraphs from a book. This is a sequel to Above and Below, an earlier, simpler game by the same designer

- Pandemic Legacy Season One, a legacy-style adaptation of the popular cooperative game, Pandemic

- Pandemic Legacy Season Two, a sequel to Pandemic Legacy Season One

- Risk Legacy, described above

- Seafall, a competitive nautical-themed game with an exploration element

The 7th Continent is a slightly controversial inclusion to this list; I have it here because it is often discussed with the others. I excluded Descent because it isn’t often considered as part of this genealogy (although perhaps it should be). Both these decisions felt a little arbitrary; I can certainly understand why building a corpus is such an important and difficult part of the text-mining process!

These comments included 4,535 unique word forms, with the length of each document varying from 4,059 words (Risk Legacy) to 2,615 (7th Continent). Voyant found the most frequent words across this corpus, but also the most distinctive words for each game. The most frequent words weren’t very interesting: game, play, games, like, campaign.*** Most of these words would probably be the most frequent for any set of game comments I loaded into Voyant! However, I noticed some interesting patterns among the distinctive words. These included:

Game Jargon referring to scenarios. That includes: “curse” for The 7th Continent (7 instances), “month” for Pandemic Legacy (15 instances), and “skirmish” for Imperial Assault (15 instances). “Prologue” was mentioned 8 times for Pandemic Legacy Season 2, in reference to the practice scenario included in the game.

References to related games or other editions. “Legacy” was mentioned 15 times for Charterstone, although it is not officially a legacy game. “Descent” was mentioned 15 times for Imperial Assault, which is based on Descent. “Below” was mentioned 19 times for Near and Far, which is a sequel to the game Above and Below. “Above” was also mentioned much more often for Near and Far than for other games; I’m not sure why it didn’t show up among the distinctive words.

References to game mechanics or game genres. Charterstone, a worker placement game, had 20 mentions of “worker” and 17 of “placement.” The word “worker” was also used 9 times for Near and Far, which also has a worker placement element; “threats” (another mechanic in the game) were mentioned 8 times. For Gloomhaven, a dungeon crawl, the word “dungeon” turned up 20 times. Risk Legacy had four mentions of “packets” in which the new materials were kept. The comments about Seafall included 6 references to “vp” (victory points). Near and Far and Charterstone also use victory points, but for some reason they were mentioned far less often in reference to those games.

The means by which the game was published. Kickstarter, a crowdfunding website, is very frequently used to publish board games these days. In this group, The 7th Continent, Gloomhaven, and Near and Far were all published via Kickstarter. Curiously, both the name “Kickstarter” and the abbreviation “KS” appeared with much higher frequency in the comments on the 7th Continent and Near and Far than in the comments for Gloomhaven. 7th Continent players were also much more likely to use the abbreviation than to type out the full word; I have no idea why this might be.

Thus, it appears that most of the words that stand out statistically (in this automated analysis) in the comments refer to facts about the game, rather than directly expressing an opinion. The exception to this rule was Seafall, which is by far the lowest-ranked of these games and which received some strongly negative reviews when it was first published. The distinctive words for Seafall included two very ominous ones: “willing” and “faq” (each used five times).

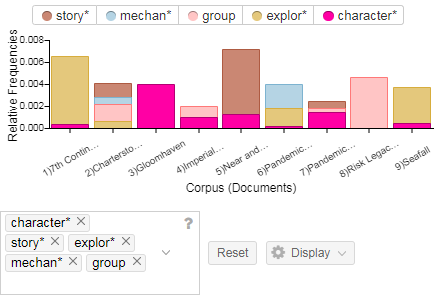

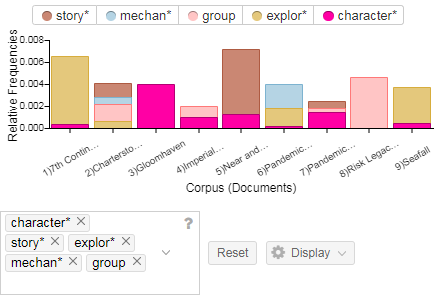

In any case, I suspected I could find more interesting information outside the selected terms. Here, again, Underwood worries me; if I select terms out of my own head, I risk biasing my results. However, I decided to risk it, because I wanted to see what aspects of the campaign game experience commenters found important or at least noteworthy. If I had more time to work on this, it would be a good idea to read through some reviews for good words describing various aspects of this style of game, or perhaps go back to a podcast where this was discussed, and see how the terms used there were (or weren’t) reflected in the comments. Without taking this step, I’m likely to miss things; for instance, the fact that the word “runaway” (as in, runaway leader) constitutes 0.0008 of the words used to describe Seafall, and is never used in the comments of any of the other games except Charterstone, where it appears at a much lower rate.**** As it is, however, I took the unscientific step of searching for the words that I thought seemed likely to matter. My results were interesting:

(Please note that, because of how I named the files, Pandemic Legacy Season Two is the first of the two Pandemics listed!)

It’s very striking to me how different each of these bars looks. Some characteristics are hugely important to some of the games but not at all mentioned in the others! “Story*” (including both story and storytelling) is mentioned unsurprisingly often when discussing Near and Far; one important part of that game involves reading story paragraphs from a book. It’s interesting, though, that story features so much more heavily in the first season of Pandemic Legacy than the second. Of course, the mere mention of a story doesn’t mean that the story of a game met with approval; most of the comments on Pandemic Legacy’s story are positive, while the comments on Charterstone’s are a bit more mixed.

Gloomhaven comments are much more about characters than any of the other terms I used; one of the distinguishing characteristics of this game is the way that characters change over time. Many of the comments also mentioned that the characters do not conform to common dungeon crawl tropes. However, the fact that characters are mentioned in every game except for two suggests that characters are important to players of campaign-style games.

I also experimented with some of the words that appeared in the word cloud, but since this post is already quite long, I won’t detail everything I noticed! It was interesting, for instance, to note how the use of words like “experience” and “campaign” varied strongly among these games. (For instance: “experience” turned out to be a strongly positive word in this corpus, and applied mainly to Pandemic Legacy.)

In any case, I had several takeaways from this experience:

- Selecting an appropriate corpus is difficult. Familiarity with the subject matter was helpful, but someone less familiar may have selected a less biased corpus.

- The more games I included, the more difficult this analysis became!

- My knowledge of the subject area allowed me to more easily interpret the prevalence of certain words, particularly those that constituted some kind of game jargon.

- Words often have a particularly positive or negative connotation throughout a corpus, though they may not have that connotation outside that corpus. (For instance: rulebook. If a comment brings up the rulebook of a game, it is never to compliment it.)

- Even a simple tool like this includes some math that isn’t totally transparent to me. I can appreciate the general concept of “distinctive words,” but I don’t know exactly how they are calculated. (I’m reading through the help files now to figure it out!)

I also consolidated all the comments on each game into a single file, which was very convenient for this analysis, but prevented me from distinguishing among the commenters. This could be important if, for example, all five instances of a word were by the same author.

*Note that there was a lag of several years due to the immense amount of playtesting and design work required for this type of game.

**Thanks to Olivia Ildefonso who helped me with this during Digital Fellows’ office hours!

***Note that “like” and “game” are both ambiguous terms. “Like” is used both to express approval and to compare one game to another. “Game” could refer to the overall game or to one session of it (e.g. “I didn’t enjoy my first game of this, but later I came to like it.”).

****To be fair, it is unlikely anyone would complain of a runaway leader in 7th Continent, Gloomhaven, Imperial Assault, or either of the Pandemics, as they are all cooperative games.