I was really excited about doing a network analysis, even though I seem to have come all the way over here to DH just to do that most librarianly of research projects, a citation analysis.

I work heavily with our institutional repository, CUNY Academic Works, so I wanted to do a project having to do with that. Institutional repositories are one of the many ways that scholarly works can be made openly available. Ultimately, I’m interested in seeing whether the works that are made available through CAW are, themselves, using open access research, but for this project, I thought I’d start a little smaller.

CAW allows users to browse by discipline using this “Sunburst” image.

Each general subject is divided into smaller sub-disciplines. Since I was hoping to find a network, I wanted to choose a sub-discipline that was narrow but fairly active. I navigated to “Arts and Humanities,” from there to “English Language and Literature,” and finally to “Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority.” From there, I was able to look at works in chronological order. Like most of the repository, this subject area is dominated by dissertations and capstone papers; this is really great for my purposes because I am very happy to know which authors students are citing and from where.

The data cleaning process was laborious, and I think I got a little carried away with it. After I’d finished, I tweeted about it, and Hannah recommended pypdf as a tool I could have used to do this work much more quickly. Since I’d really love to do similar work on a larger scale, this is a really helpful recommendation, and I’m planning on playing with it some more in the future (thanks, Hannah!)

I ended up looking at ten bibliographies in this subject, all of which were theses and dissertations from 2016 or later. Specifically:

Jarzemsky, John. “Exorcizing Power.”

Green, Ian F. P. “Providential Capitalism: Heavenly Intervention and the Atlantic’s Divine Economist”

La Furno, Anjelica. “’Without Stopping to Write a Long Apology’: Spectacle, Anecdote, and Curated Identity in Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom”

Danraj, Andrea A. “The Representation of Fatherhood as a Declaration of Humanity in Nineteenth-Century Slave Narratives”

Kaval, Lizzy Tricano. “‘Open, and Always, Opening’: Trans- Poetics as a Methodology for (Re)Articulating Gender, the Body, and the Self ‘Beyond Language ’”

Brown, Peter M. “Richard Wright’ s and Chester Himes’s Treatment of the Concept of Emerging Black Masculinity in the 20th Century”

Brickley, Briana Grace. “’Follow the Bodies”: (Re)Materializing Difference in the Era of Neoliberal Multiculturalism”

Eng, Christopher Allen. “Dislocating Camps: On State Power, Queer Aesthetics & Asian/Americanist Critique”

Skafidas, Michael P. “A Passage from Brooklyn to Ithaca: The Sea, the City and the Body in the Poetics of Walt Whitman and C. P. Cavafy”

Cranstoun, Annie M. “Ceasing to Run Underground: 20th-Century Women Writers and Hydro-Logical Thought”

Many other theses and dissertations are listed in Academic Works, but are still under embargo. For those members of the class who will one day include your own work in CAW, I’d like to ask on behalf of all researchers that you consider your embargo period carefully! You have a right to make a long embargo for your work if you wish, but the sooner it’s available, the more it will help people who are interested in your subject area.

In any case, I extracted the authors’ names from these ten bibliographies and put them into Gephi to make a graph. I thought about using the titles of journals, which I think will be my next project, but when I saw that all the nodes on the graph have such a similar appearance graphically, I was reluctant to mix such different data points as authors and journals.

As I expected, each bibliography had its own little cluster of citations, but there were a few authors that connected them, and some networks were closer than others.

Because I was especially interested in the authors that connected these different bibliographies, I used Betweenness Centrality to map these out, to produce a general shape like this:

This particular configuration of the data uses the Force Atlas layout. There were several available layouts and I don’t how they’re made, but this one did a really nice job of rendering my data in a way that looked 3D and brought out some relationships among the ten bibliographies.

Some Limitations to My Data

Hannah discussed this in her post, and I’d run into a lot of the same issues and had forgotten to include it in my blog post! Authors are not always easy entities to grasp. Sometimes a cited work may have several authors, and in some cases, dissertation authors cited edited volumes by editor, rather than the specific pieces by their authors. Some of the authors were groups rather than individuals (for instance, the US Supreme Court), and some pieces were cited anonymously.

In most cases, I just worked with what I had. If it was clear that an author was being cited in more than one way, I tried to collapse them, because there were so few points of contact that I wanted to be sure to bring them all out. There were a few misspellings of Michel Foucault’s name, but it was really important to me to know how relevant he was in this network.

Like Hannah, I pretended that editors were authors, for the sake of simplicity. Unlike her, I didn’t break out the authors in collaborative ventures, although I would have in a more formal version of this work. It simply added too much more data cleaning on top of what I’d already done. So I counted all the co-authored works as the work of the first author — flawed, but it caught some connections that I would have missed otherwise.

Analyzing the Network

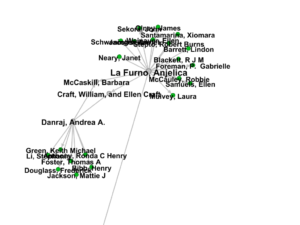

Even from this distance, we can get a sense of the network. For instance, there is only one “island bibliography,” unconnected to the rest.

Note, however, that another isolated node is somewhat obscured by its positioning: Jarzemsky, whose only connection to the other authors is through Judith Butler.

So, the two clearest conclusions were these:

- There is no source common to all ten bibliographies, but nine of them share at least one source with at least one other bibliography!

- However, no “essential” sources really stand out on the chart, either. A few sources were cited by three or four authors, but none of them were common to all or even a majority of bibliographies.

My general impression, then, is that there are a few sources that are important enough to be cited very commonly, but perhaps no group of authors that are so important that nearly everyone needs to cite them. This makes sense, since “Ethnic and Cultural Minority” lumps together many different groups, whose networks may be more visible with a more focused corpus.

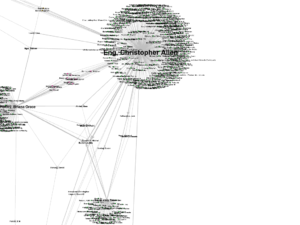

There’s also a disparity among the bibliographies; some included many more sources than others (perhaps because some are PhD dissertations and others are master’s theses, so there’s a difference in length and scope). Eng built the biggest bibliography, so it’s not too surprising that his bibliography is near the center of the grid and has the most connections to other bibliographies; I suspect this is an inherent bias with this sort of study.

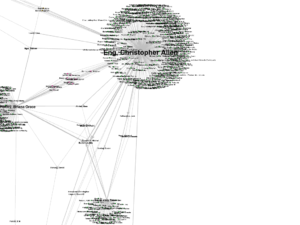

The triangle of Eng, Brickley and Kaval had some of the densest connections in the network. I try to catch a little of it in this screenshot:

In the middle of this triangle, several authors are cited by each of these authors, including Judith Butler, Homi Babhi, Sara Ahmed, and Gayle Salamon. The connections between Brickley and Eng include some authors who speak to their shared interest in Asian-American writers, such as Karen Tei Yamashita, but also authors like Stuart Hall, who theorizes multiculturalism. On the other side, Kaval and Eng both cite queer theorists like Jack Halberstam and Barbara Voss, but there are no connections between Brickley and Kaval that aren’t shared by Eng. There’s a similar triangle among Eng, Skafidas, and Green, but Skafidas has fewer connections to the four authors I’ve mentioned than they have to each other. This is interesting given the size of Skafidas’s bibliography; he cites many others that aren’t referred to in the other bibliographies.

(Don’t mind Jarzmesky; he ended up here but doesn’t share any citations with either Skafidas or Cranstoun.)

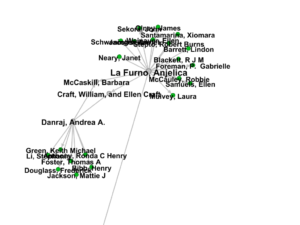

On the other hand, there is a stronger connection between Skafidas and Cranstoun. Skafidas writes on Cavafy and Cranstoun on Woolf, so they both cite modernist critics. However, because they are not engaging with multiculturalism as many of the other authors are, they have fewer connections to the others. In fact, Cranstoun’s only connection to an author besides Skafidas is to Eng, via Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (which makes sense, as Cranstoun is interested in gender and Eng in queerness). Similarly, La Furno and Danraj, who both write about slave narratives, are much more closely connected to each other than to any of the other authors – but not as closely as I’d have expected, with only two shared connections between them. The only thing linking them to the rest of the network is La Furno’s citation of Hortense Spillers, shared by Brickley.

My Thoughts

I’d love to do this work at a larger scale. Perhaps if I could get a larger sample of papers from this section of CAW, I’d start seeing the different areas that fall into this broad category of “Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority.” I’m seeing some themes already – modernism, Asian-American literature, gender, and slave narratives seem to form their own clusters. The most isolated author on my network wrote about twentieth-century African American literature and would surely have been more connected if I’d found more works dealing with the same subject matter. As important as intersectionality is, there are still networks based around specific literatures related to specific identity categories, with only a few prominent authors that speak to overlapping identities. We may notice that Eng, who is interested in the overlap between ethnicity and queerness, is connected to Brickley on one side (because she is also interested in Asian-American literature) and Kaval on the other (because she is also interested in queerness and gender).

Of course, there are some flaws with doing this the way that I have; since I’m looking at recent works, they are unlikely to cite each other, so the citations are going in only one direction and not making what I think of as a “real” network. However, I do think it’s valuable to see what people at CUNY are doing!

But I guess I’m still wondering about that – are these unidirectional networks useful, or is there a better way of looking at those relationships? I suppose a more accurate depiction of the network would involve several layers of citations, but I worry about the complexity that would produce.

In any case, I still want to look at places of publication. It’s a slightly more complex approach, but I’d love to see which authors are publishing in which journals and then compare the open access policies of those journals. Which ones make published work available without a subscription? Which ones allow authors to post to repositories like this one?

Also: I wish I could post a link to the whole file! It makes a lot more sense when you can pan around it instead of just looking at screenshots.

but it examines the network of white supremacist/white nationalist/alt-right microcelebrities on YouTube. Because many of these individuals have strong relationships with their audiences and are able to “sell” them on their ideologies, they are considered “influencers.” The report maps out the relationships among them based on their appearances on each other’s shows. It reveals connections between the extremists and those who are or describe themselves as more moderate libertarians or conservatives.

but it examines the network of white supremacist/white nationalist/alt-right microcelebrities on YouTube. Because many of these individuals have strong relationships with their audiences and are able to “sell” them on their ideologies, they are considered “influencers.” The report maps out the relationships among them based on their appearances on each other’s shows. It reveals connections between the extremists and those who are or describe themselves as more moderate libertarians or conservatives.