Alright this is a tough assignment—especially when you’re trying to map something related to a geography that has been fought over for a century and remembered and evoked in terms of metaphor.

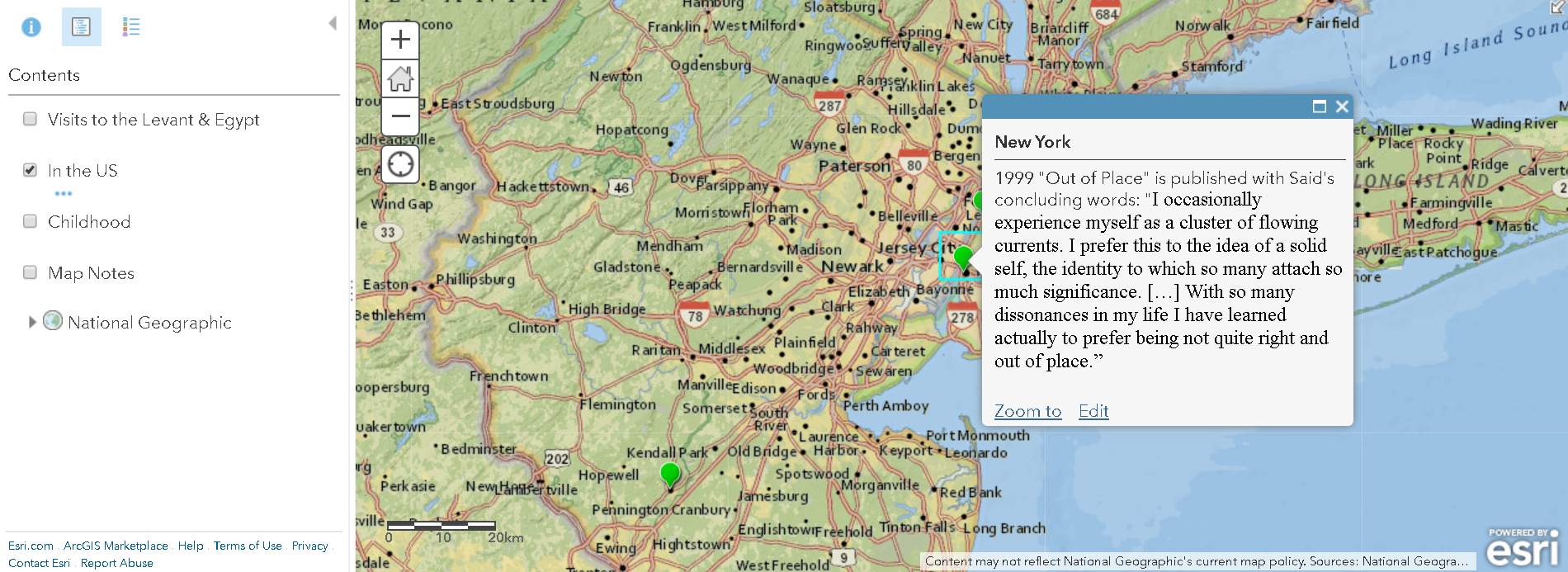

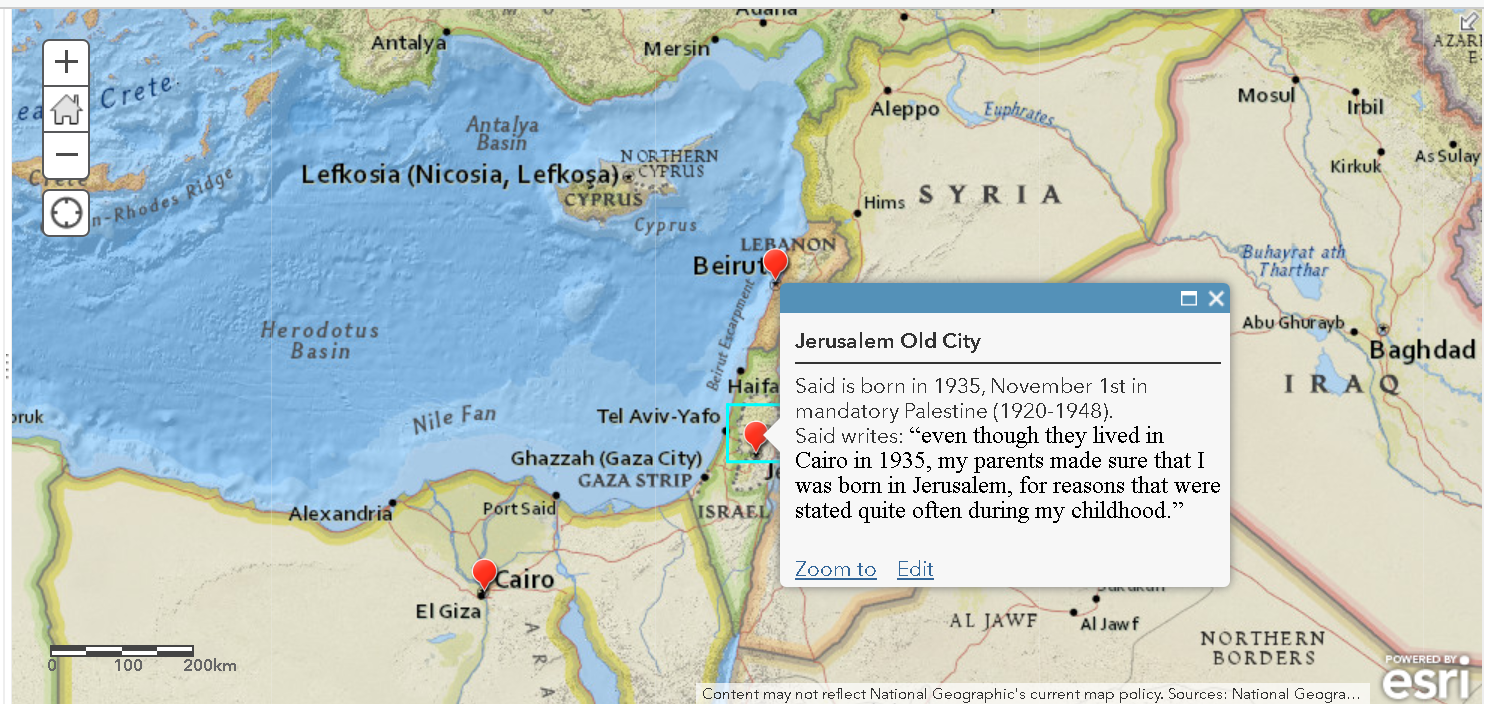

For this assignment, I chose to map the main stops of Edward Said journey (from Palestine to the US then back to Palestine). And while the map is simple (and simplistic) and straightforward, Said’s conception of place and geography is very far from that. For that reason, I have to say that the map I created doesn’t come near to capturing any claims that Said makes: partly because navigating ArcGIS requires technical training I don’t have, and because of the very assumptions underlying these maps that are rooted in a certain (western/modern) historic and intellectual development that Said largely critiques.

Briefly speaking, Said speaks of “imaginative geography-ies” by which we construct a geography/world (you may also want to check this article discussing the topic). His views on place are part of the project in social theory/post-colonial studies that took it upon itself to reconceptualize space and geography. As his nation is still in fight with an occupier, Said is thus one of the scholars who invited us to reimagine territories in the post-colonial world. He was always keen on pointing to the role of hegemonic culture in imposing delineations of geography and borders. Threads of his writing on this topic are vividly present in his book Reflections on Exile (2000) and his own autobiography Out of Place (1999) from which I seized the data for the map (I also inserted some quotes on the map). Said writes in the preface of his memoir:

“Along with language, it is geography—especially in the displaced form of departures, arrivals, farewells, exile, nostalgia, homesickness, belonging, and travel itself—that is at the core of my memories of those early years. Each of the places I lived in—Jerusalem, Cairo, Lebanon, the United States—has a complicated, dense web of valences that was very much a part of growing up, gaining an identity, forming my consciousness of myself and of others.”

Although the Presner’s discussion of “thick maps” may seem complex enough to engage with Said’s approach to geography especially when he writes: “thick maps are not simply more data on maps, but interrogations of the very possibility of data, mapping, and cartographic representational practices” (Presner, 19), it still heavily draws on a particular intellectual history in the humanities (this is actually Talal Asad critique of the interpretative Geertzian project that Presner borrows from). On the other hand, another theme we read about this week might have been more convincing to Said; that of white lying of/in maps. And while the author of that piece contends that reality is three dimensional but maps are clusters of two-dimensional graphic scale, I imagine Said jumping in and saying: they are four dimensional—with the fourth dimension being imagination tied to the wit of collective memory and individual remembering. I think, for example, of Said’s trip to Jerusalem in 1992 when he was able to visit his family home for the first time after they were forced to leave in 1948.

Few notes on the map:

I used three layers following Said’s autobiography—childhood, in the US and visits to Palestine and Egypt. I couldn’t however figure out how to make the locations appear in a chronological way…

Jerusalem, where Said was born, can be located in four different ways: Jerusalem, Israel / Jerusalem, the old city, Israel / Jerusalem East, West Bank, Palestinian territories / Jerusalem, West Bank, Palestinian territories. Said was born before the partition of Jerusalem but visited it after the East-West Jerusalem division.

Said visited Northern Palestine/Isreal in 2000 with his son—a region whose cities are named in Hebrew but Said refers to the Arabic names of towns. Ultimately, there are endless ways in which Said’s “imaginative geographies” and the ongoing contestation and fight over territories of his homeland complicate the task of mapping. I’m optimistic though, especially when I find thinking about “maps” is being undertaken in terms of “mapping”– a verb and a process rather than a given static form of geographical representation.

Overall, this exercise makes me ponder the following questions: how has the colonial project shaped the ways in which we experience/think about space and geography? How can we “decolonize” mapping as a practice in the DH? How are material and metaphorical geographies entangled? what ‘mapping’ practices may be best to express more local/particular understandings of geography and relation to place?