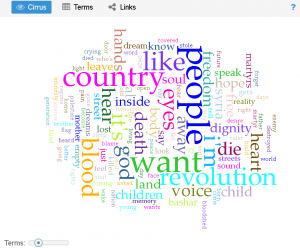

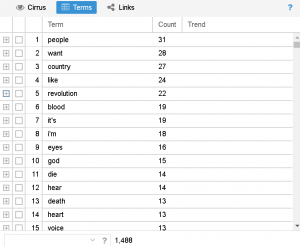

The purpose of this text mining assignment is to understand the main recurrent themes, phrases and terms in the rap songs of the Syrian revolution/war (originally in Arabic) and their relation (if any) to the overall unfolding of the Syrian war events, battles and displacement. In what follows, I will highlight the main findings and limitations of the tool for this case study.

The rap songs can be found The Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution, that is an online platform aiming to archive Syrian artistic expression (plastic art, poetry, songs, calligraphy, etc) in the age of the revolution and war. Interestingly, the website also incorporates digital tools (mapping) to map the location of demonstrations, battles, and the cities in which or for which songs were composed. It’s useful to mention that I’ve worked for the website/songs & music section since March 2016, and thus translated most of these songs lyrics. Overall, the songs cover variety of themes elucidating the horror of war, evoking the angry echo of death, and expressing aspirations for freedom and peace.

To begin with, I went over the 390 songs archived to pick the translated lyrics of the 32 rap songs stretching from 2011 until this day (take for example, Tetlayt).

https://creativememory.org/en/archives/142345/tetlayt-tilt/

I then entered the lyrics, from the most recent to the oldest, into Voyant. And here:

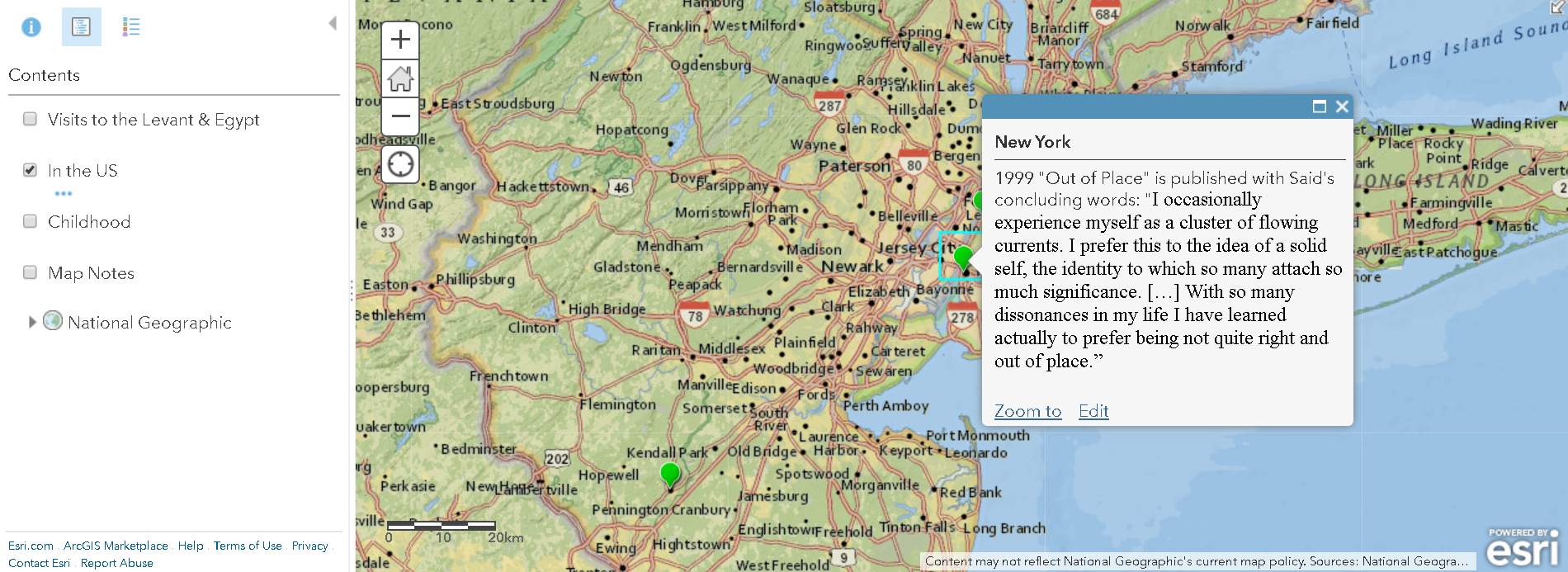

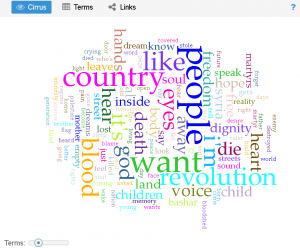

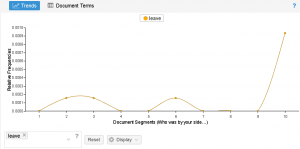

fig. 1

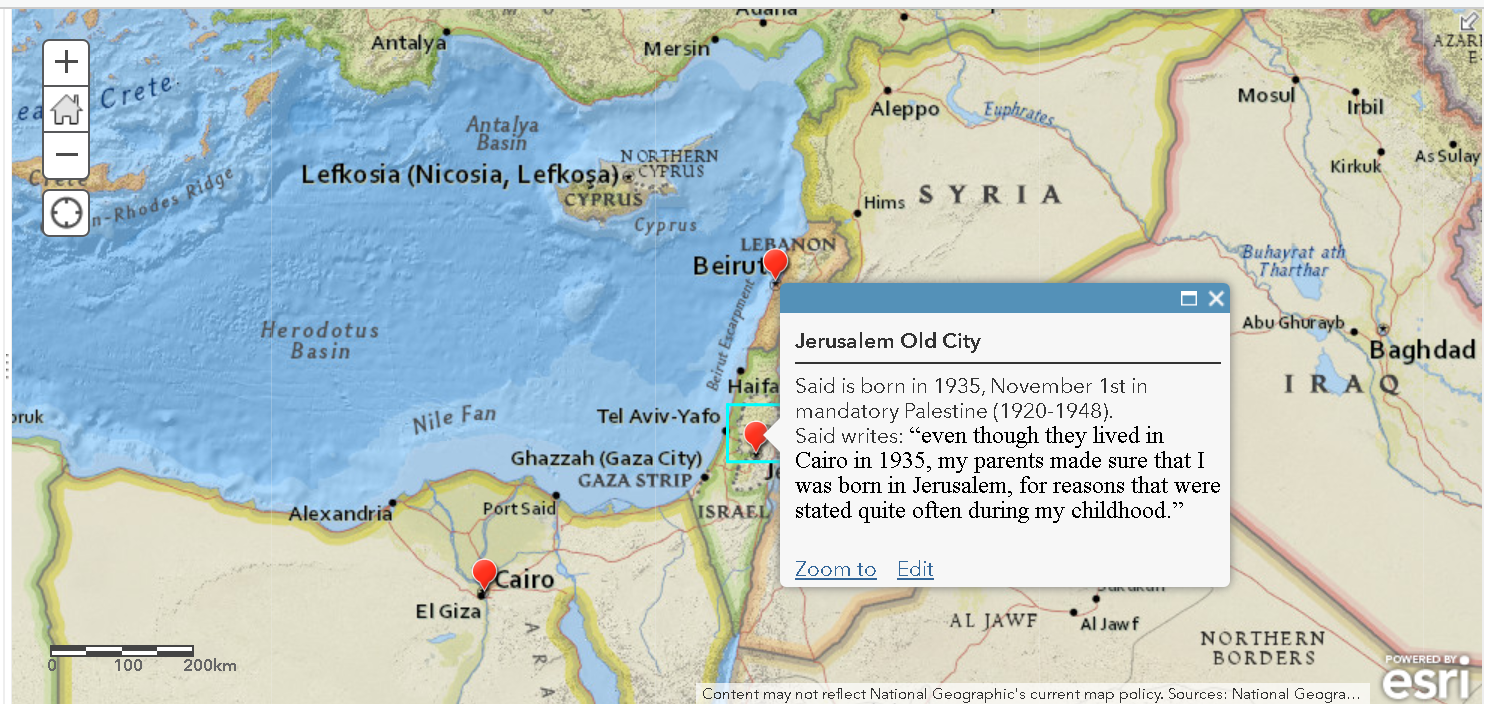

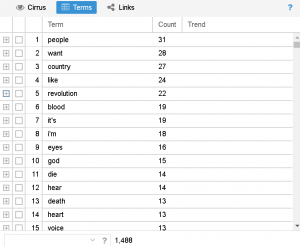

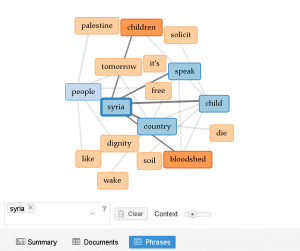

fig. 2

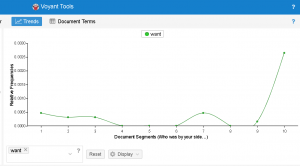

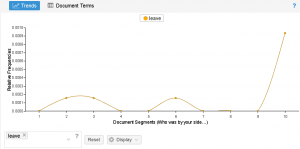

Unsurprisingly, the top 4 trends are: people, country, want, revolution (fig. 1 & 2).

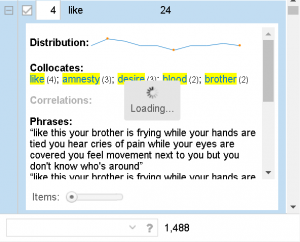

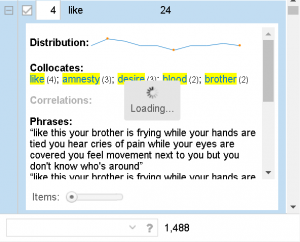

The analysis shows that the word “like” comes fourth, when the word mostly appears in a song where the rapper repeats “like [something/someone] for amplification (fig. 2 & 3).

fig. 3

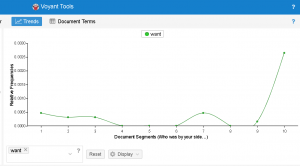

Next, I looked into when or at what phase of the revolution/war some terms were most used. It was revealing to see the terms “want” and “leave” (fig. 4 & 5) were popular at the beginning of the revolution in 2011, the time when the leading slogan was “Leave, Leave, oh Bashar” and “the people want to bring down the regime“.

fig. 4

fig. 5

fig. 6

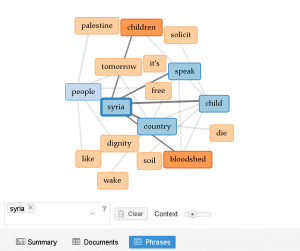

On another note, it doesn’t seem that Voyant can group the singulars and plurals of the same word (child/children in fig. 6). Or is there a way we can group several words together?

So although the analysis gives a good insight into general trends, I would argue that song texts require a tool that is adaptable to the special characteristics of the genre. After all, music reformulates language in performance, and what may be revealed as a trend in text may very well not be the case through the experience of singing and listening. Beyond text, rap songs (any song really) are a play on paralinguistic features such as tones, rhythms, intonations, pauses; and musical ones, such as scales, tone systems, rhythmic temporal structures, and musical techniques–all of which of course, a tool like voyant cannot capture. I know there are speech recognition software that are widely used for transcription, but that’s not what I’m interested in. I’m thinking of tool that do analysis of speech as speech/sound. I’m curious to know what my colleagues who did speech analysis thought of this.