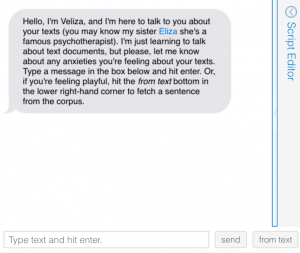

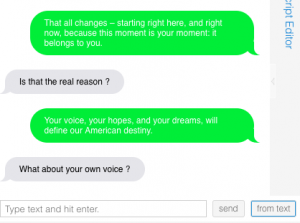

For the final project, Raven and I have created a playable beta of a game that attempts to address the intersections of online spaces, education, representation, and equity/accessibility through digital tools in learning spaces. Raven and I divided this post into two in order to explain our different angles on the same goal.

Our overall goal of this project is to find a way to increase the parameters of equity in a standard classroom, as well as offering alternative methods of knowledge creation. We want to use interactive technology as a method to give voice to those often misinterpreted or silenced within the traditional western literary canon. In education, we need to utilize multicultural texts as a means to provide diverse student-bodies with the ability to align themselves with the literature at hand. However, there is the battle of always having a group of students who will not align with what the class is studying. So, we believe that by utilizing gaming in the classroom you can expose students to different experiences such as diversity in race, disability, gender, and sexuality.

In constructing this game from a digital pedagogical perspective, I drew information from scholarship surrounding these topics, specifically in terms of educational facilities. Right now, I am using information from Tools of Exclusion: Race, Disability, and (Re)segregated Education by Beth A. Ferri of Syracuse University and David J. Connor of Columbia’s Teachers College, as well as Cathy Davidson’s (a professor here at The Graduate Center) How and Why to Structure a Classroom for Student-Centered Learning and Equality from the collection Structuring Equality: A Handbook for Student-Centered Learning and Teaching Practices, published by HASTAC. The first piece addresses the complicated issues around the interconnectedness of segregation, special education, and race. The second piece dives into how we can restructure English courses (and the classroom in general) to create a more equitable space in terms of helping students foster their identities. Helping students develop a deeper understanding of not only their own identity experience, but as well as their peers’ difference identities, helps to foster a safer and more productive classroom space.

Another piece I am drawing upon to support these notions in a more direct way is No Fun: The Queer Potential of Video Games that Annoy, Anger, Disappoint, Sadden, and Hurt by Bonnie “Bo” Ruberg. Ruberg shines a light on the aspect of “Play,” taking it in a direction of how the idea of “having fun” is so closely related to gaming. We buy and play games because we enjoy them and have fun, but not everyone has the same type of fun with certain things. She continues to talk about how “no-fun” can be a tool for addressing uncomfortable topics that need to be talked about. We have developed a game based around this notion because topics of prejudice are uncomfortable topics in whichever form they take. So we are using a game as a platform to widen the perspective of students using emotional experiences linked to the said game.

In relation to Digital Humanities, we believe that platforms like Twine are very user-friendly, and definitely open up the opportunity to scaffold the assignments (like Ryan Cordell suggests doing in How Not to Teach Digital Humanities) so that students can naturally be exposed to digital humanities in all of its glory. Creating these narrative-based games offers up an entirely new way to write and create public knowledge, two very important aspects of academia. This could lead to potential workshops on using different game-creation platforms and how to implement them pedagogically.