Hi everyone,

You all already saw Jennifer and I present, but here are more details about our final project — in a blog post format. We also tentatively selected a name for our nonprofit news curation tool/website — “Nonprofit News Board.”

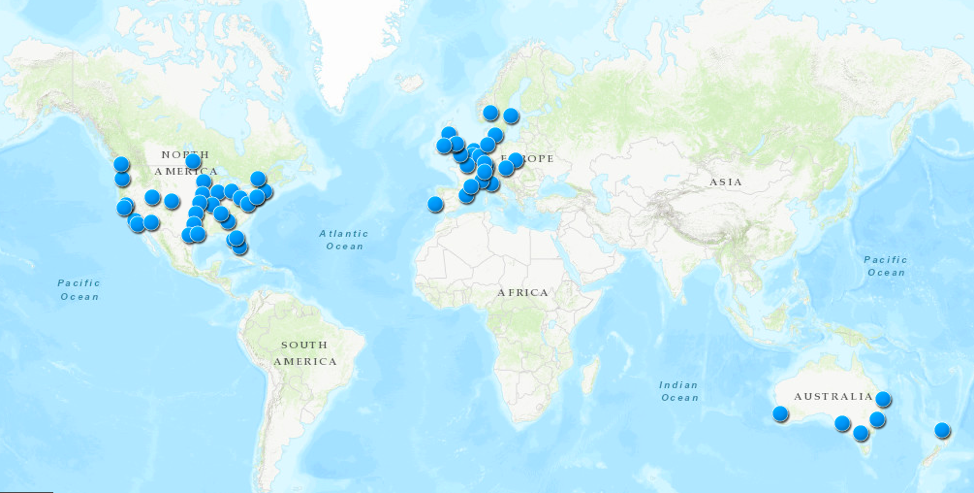

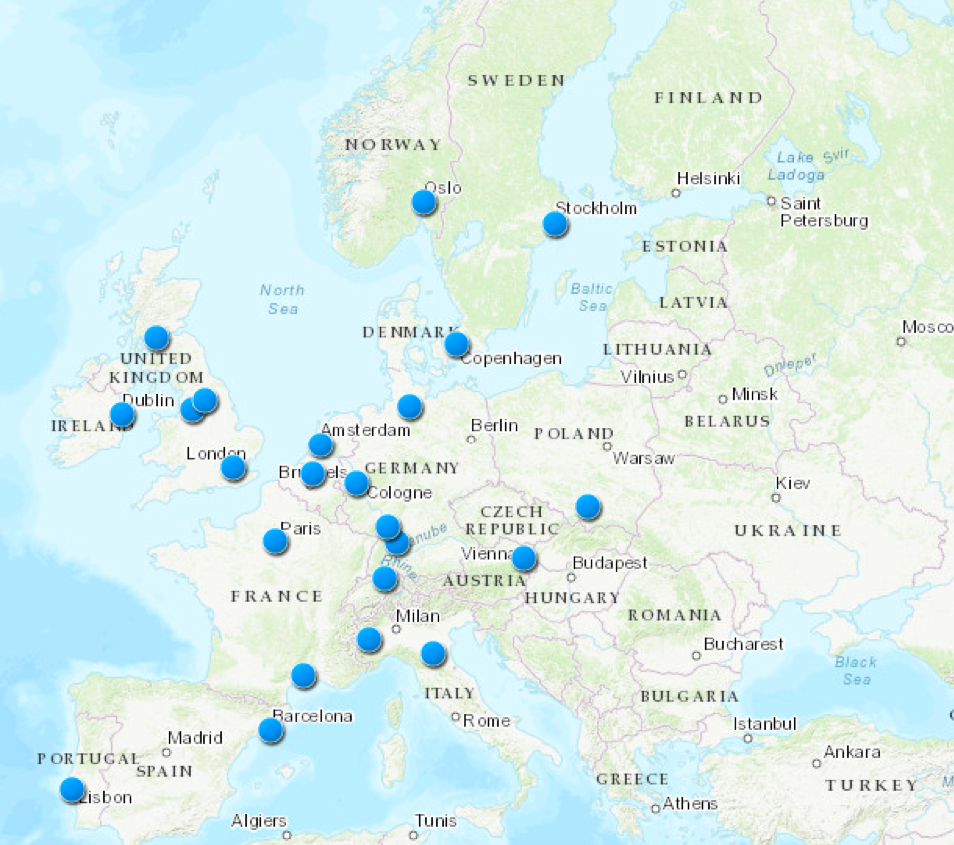

We are proposing the creation of the tentatively-named “Nonprofit News Board,” a website that will aggregate and curate the news produced by nonprofit media outlets. By gathering the links to their work in one location, and offering different ways of presenting the stories — including through the use of visualizations — we seek to facilitate access to and awareness of this sector, especially at a time when the news media in general face dire circumstances: financial insecurity, the proliferation of inaccurate information masquerading as news, newsrooms facing cutbacks and layoffs if not being shuttered altogether, and hostility from those in power. In the last 10-15 years, numerous nonprofit news startups emerged, in many cases to fill in the gaps left by the closing of many local newsrooms and produce in-depth, critical and nonpartisan coverage of government, education, health and other issues that serve the public interest. These outlets, many of whom represent a particular region of the country or focus on specific topics, aim to inform and educate readers.

Through building a structure that presents these kind of stories, we strive to spotlight and promote work that has undergone extensive research and verification. The site would serve as a remedy for the spread of misinformation and give visitors an innovative one-stop alternative to news that is produced by organizations driven by the need to turn a profit and to be the first on a story. Visitors will find in one location the not-so-breaking news; stories about the aftermath of so-called breaking news; and the investigations months and years in the making.

By driving traffic to nonprofit sites and ideally helping to establish a following for them, a greater number of people will, story by story, be better informed about the news they consume. We will examine sites that aggregate and curate the news and consider how to build on those examples to best produce a unique product in a time of heightened public awareness of the media industry.

While journalism and the humanities are considered two distinct fields, the principles of nonprofit journalism overlap with those of the humanities. At the core of both, practitioners engage in observing and documenting human societies and experiences through critical thought, research and communication. Through the study of arts and culture, the humanities inform students and scholars of the similarities of seemingly disparate people and communities, or at least encourage them to observe and understand societies and see the many sides of the human experience. In a similar fashion, the mission of most nonprofit media outlets includes giving a platform to the issues and voices often ignored by mainstream news entities. This can stir up empathy in readers and help them realize the experiences shared between different populations. In this regard, highlighting the nonprofit media sector effectively also promotes the principles of the humanities and establish connections between the two disciplines.