I start with a provocation from Ted Underwood in answer to his own question of whether it is necessary to have a large collection of texts to do text mining (well, distant reading, really):

This is up for debate. But I tend to think the answer is “yes.”

Not because bigger is better, or because “distant reading” is the new hotness. It’s still true that a single passage, perceptively interpreted, may tell us more than a thousand volumes.

But if you want to interpret a single passage, you fortunately already have a wrinkled protein sponge that will do a better job than any computer. Quantitative analysis starts to make things easier only when we start working on a scale where it’s impossible for a human reader to hold everything in memory. Your mileage may vary, but I’d say, more than ten books? (Underwood, “Where to start with text mining”)

Naturally, my text mining investigation transgresses this theory and, ultimately, doesn’t disprove it.

At first, I wanted to compare translations of Rimbaud’s Illuminations, the first by Wallace Fowlie and the second by John Ashbery. I wasn’t able to easily get the latter in digital form, so I looked at a set of corpora I had “lying around” and chose to do the same with translations of Proust I found in my digital desk drawer.

The canonical translation of A La Recherche du Temps Perdu was, for many years, the C.K. Scott Moncrieff one. More recently, Terence Kilmartin reworked the Moncrieff translation. And then D.J. Enright reworked Moncrieff in light of the Kilmartin translation. In the process, the translated title “Remembrance of Things Past” became “In Search of Lost Time”.

In attempting to avoid lost time myself, I chose to render just the first volume Swann’s Way (in both).

Clearly this is not ten texts, but I am very interested in whether empirical investigations into different translations of an individual work can uncover interesting information about translation in general; and many other questions about translation that I certainly don’t address here. Here is just a start.

Methodology:

I started with an html file of Enright’s translation of Swann’s Way, copied it into a plain text file and started to clean it manually. This involved removing a bunch of text from the beginning and end. I did the same for the Moncrieff translation, except I had an epub file of that which I converted to plain text using an online conversion tool. The Moncrieff translation had separated the Place Names: the Name section from the end of the Enright file, which was better left off anyway.

I made the assumption that this process wasn’t introducing any error that wasn’t already in the texts as I got them. If I were doing this for an actual study, I would not make that assumption.

My first thought was to try to reproduce the methodology of a Stanford group that had compared translations of Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. This would have required me to use two tools, Python NLTK to “tokenize” the texts into sentences and then Stanford’s Lexical Parser to analyze them syntactically. As I sat down to do this this weekend, away from home in the cold north with family and under conditions of intermittent and slow internet, I realized the time investment was beyond the scope of a weekend. Syntactic analysis is thus a huge gap in my efforts — and was really what I was interested in initially.

Coming back home, I decided to see what I could do with Voyant. So I used the upload function from the Voyant-tools landing page and selected both texts (separate plain text files), then clicked the circus-like “Reveal” button.

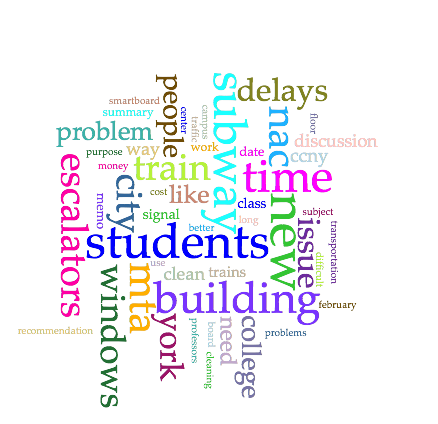

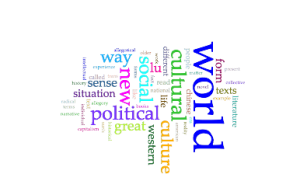

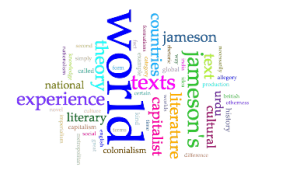

There were a lot of proper names and a few other terms (such as “swann”, “odette”, “mme”, etc.) that I didn’t think were useful, so I used the options button in the Cirrus tool to add “stop words” to filter them out and then applied that filter globally.

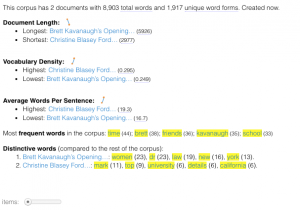

I used the Summary for a lot of my statistics because it was the clearest spot to see big picture comparisons between the texts. I also explored every tool available, switching them into and out of display panes. For my purposes, the most useful were Document Terms, Trends, Summary, and Terms. I think I could have used Contexts more if I were asking the right questions. The Reader did not help much at all because the corpora were listed one after the other rather than side by side.

I also consulted with WordNet to come up with words that surrounded the concept of remembering and memory. I did not see a way to do this, or invoke outside help, from within Voyant, so I just went to the source.

The Reveal:

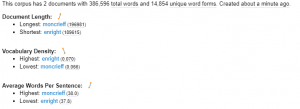

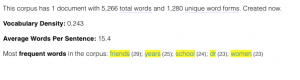

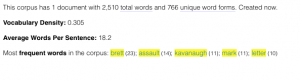

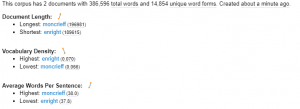

One thing that jumped out is the total word count comparison. Moncrieff uses 196981 words to Enright’s 189615 — a difference of 7366 words, or 3.8% more words in Moncrieff than Enright. At the same time Enright’s vocabulary density is consistently higher, 0.4% over the course of the novel and 0.7% in the Overture itself. This suggests that Enright’s translation is more economical — dare I say “tighter”? Of course, the semantic richness of the two texts and how closely they “capture” the original are not questions these stats answer.

Doing some simple math by dividing the total number of words by the average sentence length (why doesn’t Voyant just give the actual # of sentences?), shows that Moncrieff has about 5184 sentences to Enright’s 5016. Given that Enright’s average sentence size is shorter, he has clearly not increased the length of his sentences to “fit in” the extra clauses/phrases that Moncrieff uses. Does this mean he is leaving things out? Or is it further evidence of Enright’s greater efficiency? If one is translating sentence for sentence from the original, how does one end up with such a discrepancy of sentences (168 difference) without combining them? Unfortunately, I don’t immediately see a way of answering this question from a distance.

Comparing the two texts for word frequency for the top words didn’t show much difference. However, the differences are magnified by the relative word counts of the corpora. For example “time” — a crucial word for the work — looking for it in the “Document Terms” tool shows that it occurred 429 times in Enright to 420 for Moncrieff, but dividing by approximate sentence count, shows “time” occuring at a rate of about 0.086 per sentence in Enright whereas Moncrieff’s per sentence frequency of “time” is about 0.081. Projecting Enright’s frequency to the length of Moncrieff’s text, we would get about 446 instances of “time” in the later translation, which is 1.06 times as much as the earlier translation.

Let’s look then at the ways “time” can be used. There is some ambiguity to the word “time” which can be fun but obfuscating. Given “time”s ambiguity, I wondered if perhaps the additional uses of it indicated something less precise in Enright. So I looked at the text itself in a few spots.

I didn’t think I was going far afield to grab “time” and drill down with the word. Not only does it have a lot of vectors of meaning and ways to be used, but it is central to the theme of the whole work (i.e. Remembrance of Things Past, In Search of Lost Time). Seeing how it is invoked by the two translators could tell us a lot about how they see “time” operating in the work as a whole.

Comparing the first paragraphs of the two texts:

Enright:

For a long time I would go to bed early. Sometimes, the candle barely out, my eyes closed so quickly that I did not have time to tell myself: “I’m falling asleep.” And half an hour later the thought that it was time to look for sleep would awaken me; I would make as if to put away the book which I imagined was still in my hands, and to blow out the light; I had gone on thinking, while I was asleep, about what I had just been reading, but these thoughts had taken a rather peculiar turn; it seemed to me that I myself was the immediate subject of my book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V. This impression would persist for some moments after I awoke; it did not offend my reason, but lay like scales upon my eyes and prevented them from registering the fact that the candle was no longer burning. Then it would begin to seem unintelligible, as the thoughts of a previous existence must be after reincarnation; the subject of my book would separate itself from me, leaving me free to apply myself to it or not; and at the same time my sight would return and I would be astonished to find myself in a state of darkness, pleasant and restful enough for my eyes, but even more, perhaps, for my mind, to which it appeared incomprehensible, without a cause, something dark indeed.

I would ask myself what time it could be;

Moncrieff:

FOR A LONG time I used to go to bed early. Sometimes, when I had put out my candle, my eyes would close so quickly that I had not even time to say ‘I’m going to sleep.’ And half an hour later the thought that it was time to go to sleep would awaken me; I would try to put away the book which, I imagined, was still in my hands, and to blow out the light; I had been thinking all the time, while I was asleep, of what I had just been reading, but my thoughts had run into a channel of their own, until I myself seemed actually to have become the subject of my book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V. This impression would persist for some moments after I was awake; it did not disturb my mind, but it lay like scales upon my eyes and prevented them from registering the fact that the candle was no longer burning. Then it would begin to seem unintelligible, as the thoughts of a former existence must be to a reincarnate spirit; the subject of my book would separate itself from me, leaving me free to choose whether I would form part of it or no; and at the same time my sight would return and I would be astonished to find myself in a state of darkness, pleasant and restful enough for the eyes, and even more, perhaps, for my mind, to which it appeared incomprehensible, without a cause, a matter dark indeed. I would ask myself what o’clock it could be;

- Time 1: “For a long time” — a temporal period with some vagueness

- Time 2: “I did not have time” — time as a resource in which to accomplish a goal

- Time 3: “the thought that it was time to go to/look for sleep” — a discrete moment suggesting a demand

- Time 4: “I had been thinking all the time, while I was asleep” — only in Moncrieff, vague use of a temporal period, perhaps rendered better in Enright’s interpretation “I had gone on thinking, while I was asleep,” which feels more accurate to the process described.

- Note: I’m leaving out “sometimes”

Nothing here indicates a lack of precision on Enright’s part. Indeed, his paragraph reads better, is more modern and succinct.

Over and over as I looked at statistics, contexts, and collocations, I found that being able to look at the texts “side by side” was crucial if I wanted to investigate something, or test a theory. I didn’t believe that Voyant was showing me what I wanted to see, but was leading me to things that I might want to look at more closely. I’m sure that my close reading bias is an influence here — but Underwood’s provocation continues to loom.

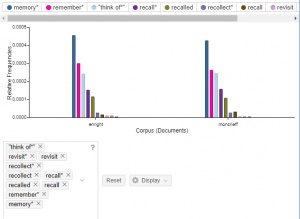

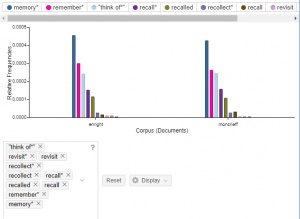

Riffing on this, I thought perhaps I could look at the way the two authors approach the concept of memory — perhaps the most important theme of the entire work. This time (pun intended), I was working from a concept rather than a particular word. So, in lieu of having a way to look at a concept in Voyant directly, I pulled a set of terms from WordNet around the idea of “remembering”, such as: recall, remember, revisit, retrieve, recollect, think of, think back, etc. I then added “memory” to the mix and fed the set of terms into the trend tool. I noticed that the search field would dynamically take my search term and return me the option of, say, “remember” and “remember*”. “Remember*” seemed to look for words with “remember” as a root. Phew. So I didn’t have to include past forms like “remembered”.

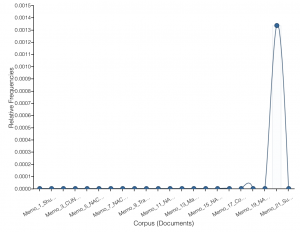

I’ll include the graph, but the upshot is that the distribution of these words was very close in the two translations as well as the total use of the concepts. Again, I had to do some extra math to compare these. I didn’t see a way in Voyant to group them under a user-defined concept and count from there.

This is already getting very long, so I won’t show the side by side comparisons that “remember” led me to. It is clear, however, that some of the most interesting differences between the translations come at the sentence construction layer. Crucial sentences have significantly different syntactic constructions. I could get a sense of what the initial wordcount statistics led me to surmise, the economy of Enright’s translation over Moncrieff’s, and was struck by what I would consider “improvements” both stylistically and semantically, by going to the texts themselves to confirm.

Conclusions:

First off, disclaimer: I need to read the stats books Patrick sent out to be better able to analyze the data I did get and assess its significance. To do a study of translations, I should be more well versed in Translation Theory and literary translation theory in particular.

Second, I’m not sure comparing translations of a single work is a good application for distant reading; as Underwood suggests, the human brain is better at comparing smaller data sets. And there aren’t many data sets including translations of larger works that would generate enough volume to make sense. On the other hand, taking a larger view of the trends in translation over a longer span of time, with multiple texts, could be very interesting. Further, I wonder what I could have unearthed, at a more distant view, if I had been able to drill down to syntactic analysis, sentence construction, etc.

The focus of this assignment was to get started with this sort of tool, to play around with it. As a result of my “play” and the constraints of what I chose to play with, I found myself jumping back and forth between distant reading and close reading, finding more in the latter that seemed meaningful to me. But I was struck by what some basic stats could tell me — giving me some areas to further investigate in close reading — such as the implications of the disparity in number of sentences and word count.

Now to Voyant. Once I had “cleaned” my texts, it was incredibly simple to get up and running in Voyant. In order to compare different texts in the same upload, it took some digging, however. I would suggest uploading files, because then Voyant knows you have separate corpora. The information is there, mostly, but sometimes hidden; for example the Summary tool compares word count, vocabulary density and average sentence lengths, but then combines the corpora to determine the most frequently used words. It was only in the Document Terms tool that I could see the word counts separated by corpus — and this only on words I selected myself, either by clicking on them somewhere else or entering them in the search field. I would like to see a spread of most commonly used words by corpus.

The Terms tool is fantastic for drilling down to a terms collocations and correlations. Again, I wish that it had separated the stats by corpus, or given us a way to do that without invoking other tools. The Topics tool confused me. I’m not sure what it was doing ultimately; I could tell it was clustering words, but I couldn’t tell the principle. I will need to look at this more.

So, Voyant was very easy to get up and going, had a short learning curve to explore the significance of the tools provided and can really get at some excellent data on the macro level. It becomes harder to use it to customize data views to see exactly what you want to see on a more micro level. I don’t fault Voyant for that. It’s scope is different. As a learning tool for me, I am very grateful to have given it a shot. I might use it in the future in conjunction with, say nltk, to streamline my textual investigations.

but it examines the network of white supremacist/white nationalist/alt-right microcelebrities on YouTube. Because many of these individuals have strong relationships with their audiences and are able to “sell” them on their ideologies, they are considered “influencers.” The report maps out the relationships among them based on their appearances on each other’s shows. It reveals connections between the extremists and those who are or describe themselves as more moderate libertarians or conservatives.

but it examines the network of white supremacist/white nationalist/alt-right microcelebrities on YouTube. Because many of these individuals have strong relationships with their audiences and are able to “sell” them on their ideologies, they are considered “influencers.” The report maps out the relationships among them based on their appearances on each other’s shows. It reveals connections between the extremists and those who are or describe themselves as more moderate libertarians or conservatives.