I’ve been hearing more and more about building corpora of student writing of late, and while I haven’t actually consulted any of these, I was happy to have the opportunity to see what building a small corpus of student writing would be like in Voyant. I was particularly excited about using samples from ENGL 21007: Writing for Engineering which I taught at City College in Spring 2018, because I had a great time teaching that course and know the writing samples well.

Of the four essays written in ENGL 21007 I chose the first assignment, a memo, because it is all text (the subsequent assignments contain graphs, charts and images and I wasn’t sure how these would behave in Voyant). I downloaded the student essays from Blackboard as .docx and redacted them in Microsoft Word. This was a bad move because Microsoft Word 365 held on to the metadata, so student email accounts showed up when I uploaded my corpus to Voyant. I quickly removed my corpus from Voyant and googled how do I remove the metadata, then decided that it would be faster to convert all .docx to .pdf and redact them with Acrobat Pro (I got a one-week free trial) so I did this, zipped it up and voila.

22 Essays Written by Undergraduate Engineering Majors at City College of New York, Spring 2018

I love how Voyant automatically saves my corpus to the web. No registration, no logging in and out. There must be millions of corpora out there.

I was excited to see how the essays looked in Voyant and what I could do with them there. I decided to get the feeling of Voyant by first asking a simple question: what did students choose to write about? The assignment was to locate something on the City College campus, in one’s community or on one’s commute to college that could be improved with an engineering solution.

Cirrus view shows most frequently used words in 22 memos written by engineering majors in ENGL 21007

What strikes me as I look at the word cloud is that students’ concern with “time” (61 occurrences) was only slightly less marked than the reasonable – given that topics had to be related to the City College campus – concern with “students” (66 occurrences). I was interested to see that “escalators” (48 occurrences) got more attention than “windows” (40 occurrences), but I think we all felt strongly about both. “Subway” (56 occurrences) and “MTA” (50 occurrences), which are the same thing, were a major concern. Uploading samples of student writing and seeing them magically visualized in a word cloud summarizes the topics we addressed in ENGL 21007 in a useful and powerful way.

Secondly and in a more pedagogical vein, I wanted to see how Voyant could be used to measure the achievement of course learning outcomes in a corpus of student writing. This turned out to be a way more difficult question than my first simple what did students write about. The challenge lies in figuring out what query will tell me whether the eight English 21007 course learning outcomes listed on the CCNY First Year Writing Program website were achieved through the essay assignment that produced the 22 samples I put in Voyant, and whether evidence of having achieved or not achieved these outcomes can be mined from student essays with Voyant. Two of the course learning outcomes seemed more congenial to the Memo assignment than others. These are:

“Negotiate your own writing goals and audience expectations regarding conventions of genre, medium, and rhetorical situation.”

“Practice using various library resources, online databases, and the Internet to locate sources appropriate to your writing projects.”

To answer the question of whether students were successful in negotiating their writing goals would require knowing what their goals were. Not knowing this, I set this part of the question aside. Audience expectations was easier. In the assignment prompt I had told students that the memo had to be addressed to the department, office or institution that had the power to approve the implementation of proposed engineering solutions or the power to move engineering proposals on to the department, office or institution that could eventually approve these. There are, however, many differently named addressees in the student memos I put in this corpus. Furthermore, addressing the memo to an official body does not by itself achieve the course learning outcome. My question therefore becomes, what general conventions of genre, medium and rhetorical situation do all departments, offices or institutions expect to see in a memorandum, and how do I identify these in a query? What words or what combinations of words constitute memo-speak? To make things worse (or better :)!), I had told students that they could model their memos on the examples of memos I gave them or, if they preferred, they could model them differently so long as they were coherent and good. I therefore cannot rely on form to measure convention of genre. I’m sorry to say I have no answers to my questions as of yet; I’m still trying to figure out how to ask my corpus if students negotiated audience expectations regarding conventions of genre, medium and rhetorical situation (having said this, I think I can rule out medium, because I asked students to write the memo in Microsoft Word).

The second course learning outcome I selected – that students practice using library resources, online databases and the internet – strikes me as more quantifiable than the first.

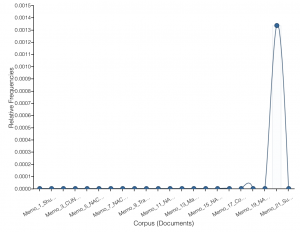

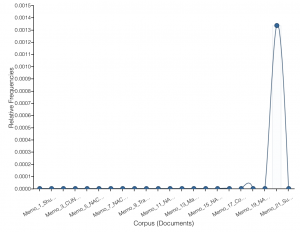

Only one of 22 memos contains the words “Works Cited”

Unfortunately, I hadn’t required students do research for the memos I put in the corpus. When I looked for keywords that would indicate that students had done some research Voyant came up with one instance of “Bibliography,” one instance of “Works Cited” and no instances of “references” or “sources.” The second course learning outcome I selected is not as congenial to the memo assignment – or the memo assignment not congenial to that course learning outcome – as I first thought.

I tried asking Veliza the bot for help in figuring out whether course learning outcomes had been achieved (Veliza is the sister of Eliza, a psychotherapist, and says she isn’t too good at text analysis yet). Veliza answers questions with expressions of encouragement or more questions but she’s not much help. The “from text” button in the lower right corner of the Veliza tool is kind of fun because it fetches sentences from the text (according to what criteria I haven’t a clue) but conversation quickly gets surreal because Veliza doesn’t really engage.

In conclusion, I am unsure how to use text mining to measure course learning outcomes in student writing done in 200-level courses. I think that Voyant may work better for measuring course learning outcomes in courses with more of an emphasis on vocabulary and grammar, such as, for example, EAL. It’s a bit of a dilemma for me, because I think that the achievement of at least some course learning outcomes should be measurable in the writing students produce in a course.

In it you’ll find notes I took of some of Olivia’s and Javier’s suggestions interspersed with a lot of nonsense I wrote as I feverishly followed Olivia’s directions, and an odd assortment of photos I pulled at random from my files. I like how the little dog becomes the big dog; that was a lucky accident. You’ll figure out how to use ESRI easily if you just dive in and play around.

In it you’ll find notes I took of some of Olivia’s and Javier’s suggestions interspersed with a lot of nonsense I wrote as I feverishly followed Olivia’s directions, and an odd assortment of photos I pulled at random from my files. I like how the little dog becomes the big dog; that was a lucky accident. You’ll figure out how to use ESRI easily if you just dive in and play around.

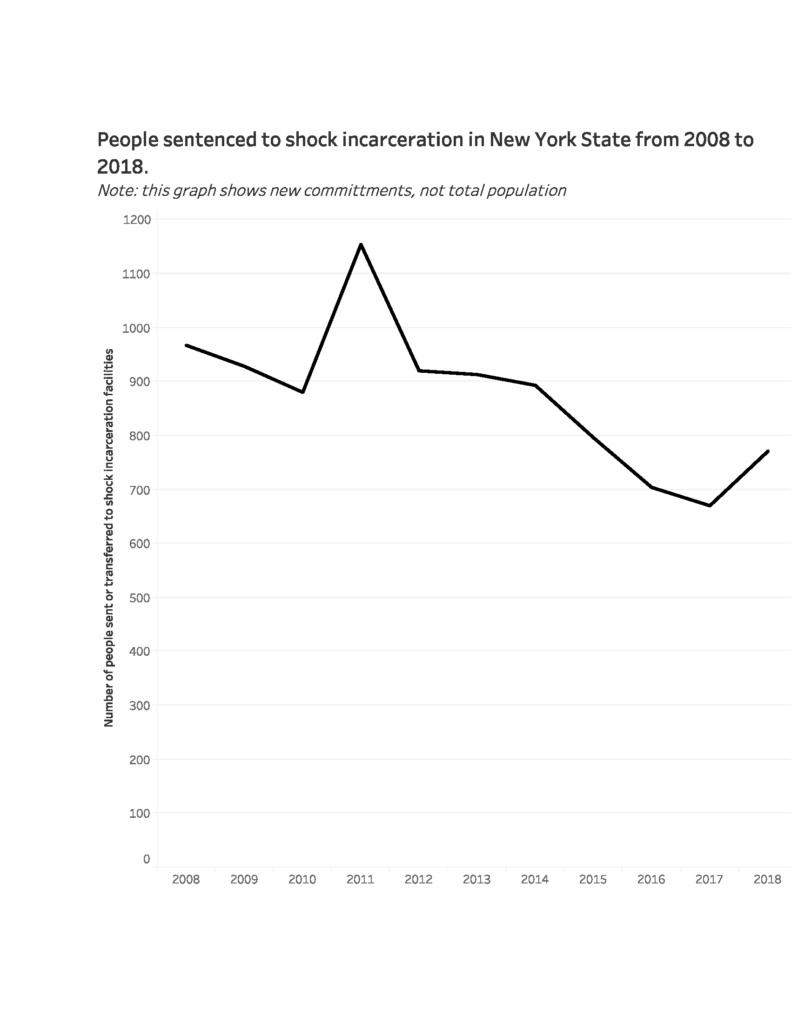

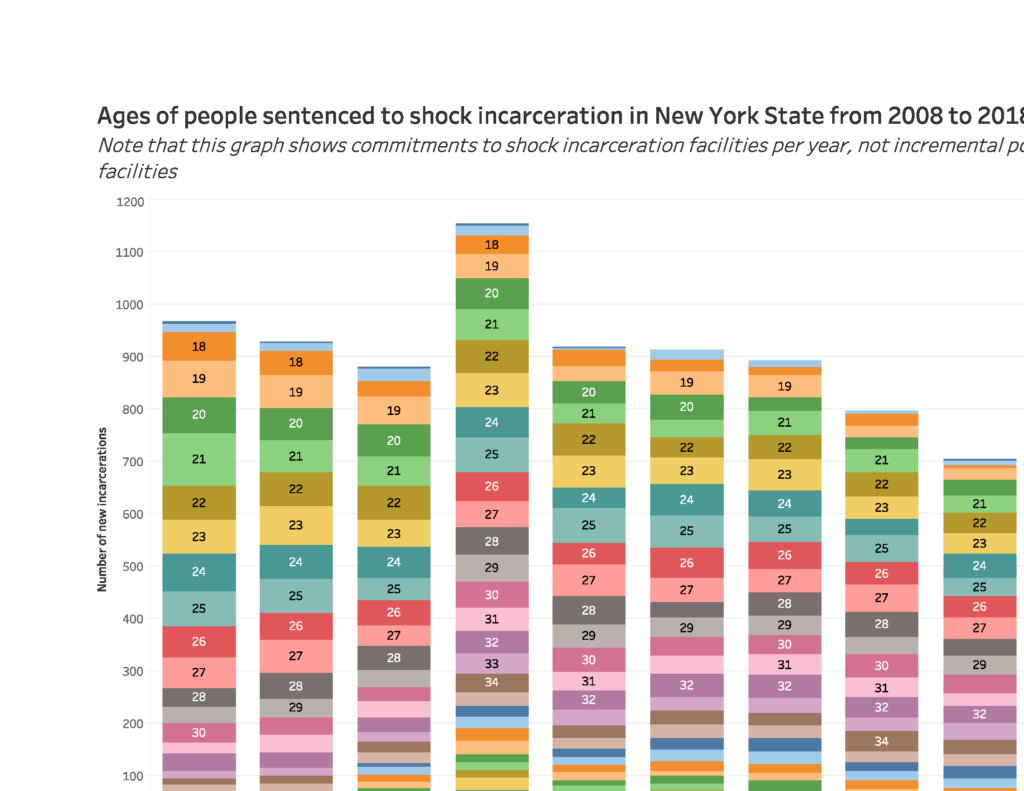

Phew, that’s all for now. See it on Tableau, there’s no comparison.

Phew, that’s all for now. See it on Tableau, there’s no comparison.