I really enjoyed Miriam Posner’s piece this week See No Evil because it brought up a common theme we’ve seen within the readings on digital humanities: how and why certain data/content is deliberately concealed or silenced and thus, what it means to utilize a variety of data software tools to draw attention to, address or even how data software tools contribute to the silencing or concealment of data/content. Personally, I am particularly interested in what we can uncover and learn from these concealings and silences to better address injustices and inequalities within society.

Prior to reading this article, my knowledge of the supply chain process was sparse and frankly, in the past, I have spent very little time considering the origins of where my goods came from. As an Amazon Prime member, I have the luxury of receiving my packages within 48 hours of ordering (2-day shipping) and as a person who has used the new Prime Now feature I have even received my goods the same day and within hours of ordering. I just want my items and I want them as soon as possible. Last minute birthday presents? No problem! Groceries delivered to my door? Delivered on the same day. The convenience is unreal.

However, what is at stake with my convenience? Should I know or care about the entire process for the supply chain of my goods? Why don’t I know more about the process? Am I part of the problem? Oh god, I am most definitely part of the problem.

Posner argues that the lack of knowledge of the supply chain process is deliberate, both to the company through the software they use and in turn the consumer; “By the time goods surface as commodities to be handled through the chain, purchasing at scale demands that information about their origin and manufacture be stripped away.” This is done deliberately by companies as a means to create an ignorance of the very specifics of how a product is created and transported, leaving companies turning a blind eye to horrifying work conditions and labor practices. This allows companies to avoid accountability for these work conditions and labor practices and pivot back to the consumer.

The consumers are in the dark, unaware of what their wants and needs for products mean for the working conditions and labor practices that impact those who are ensuring we receive our goods. Would consumers change their minds about a company if they truly knew what’s behind the scenes of receiving goods? I think most certainly. As consumers should we demand to know the details of a company’s supply chain process? Perhaps we should be more active consumers and demand this knowledge by holding the companies that we purchase from to a higher standard. We, as consumers, could push companies to begin taking accountability for their supply chain process. Let’s do it!

However, we, as a society, rely on this darkness as a means to enable globalization and capitalism even when it means terrible labor practices and the suffering of those in the supply chain. We’ve exchanged scale, globalization, and capitalism for human rights. Globalization and capitalism are only possible through a lack of accountability companies and consumers are able to have regarding the goods they receive. Posner states “We’ve chosen scale, and the conceptual apparatus to manage it, at the expense of finer-grained knowledge that could make a more just and equitable arrangement possible.” Posner’s example of the supply chain process and software was the perfect example to highlight how deeply embedded capitalism and globalization is within society and the ways capitalism and globalization manifest themselves even in software programs.

So my question is where do we go from here?

By the end of the piece, Posner touches on the potential of visibility for supply chain software and programming, but ultimately the problem is more than just software. We must, as a society, agree to see, even if it is traumatic (as she references) for us to know the truth.

I believe that knowledge about things like the supply chain process may disrupt the structures of globalization and capitalism we’ve come to rely on, which may lead to more equitable working conditions and practices for all. We as consumers should do better at demanding to know the supply chain process and accept that it may mean that we see some things we don’t want to see and lose some convenience. Ultimately being in the light may help us be more understanding and empathetic to others lives and create better working conditions for all. Let’s turn on the light and be brave. Let’s do better.

PS: (Slightly related but kind of a sidebar, Comedian Hasan Minaj just did an episode from his new Netflix show Patriot Act on Amazon discussing some different aspects on their growth and the impacts this has on their supply chain. Here is a link to a YouTube video of the episode.)

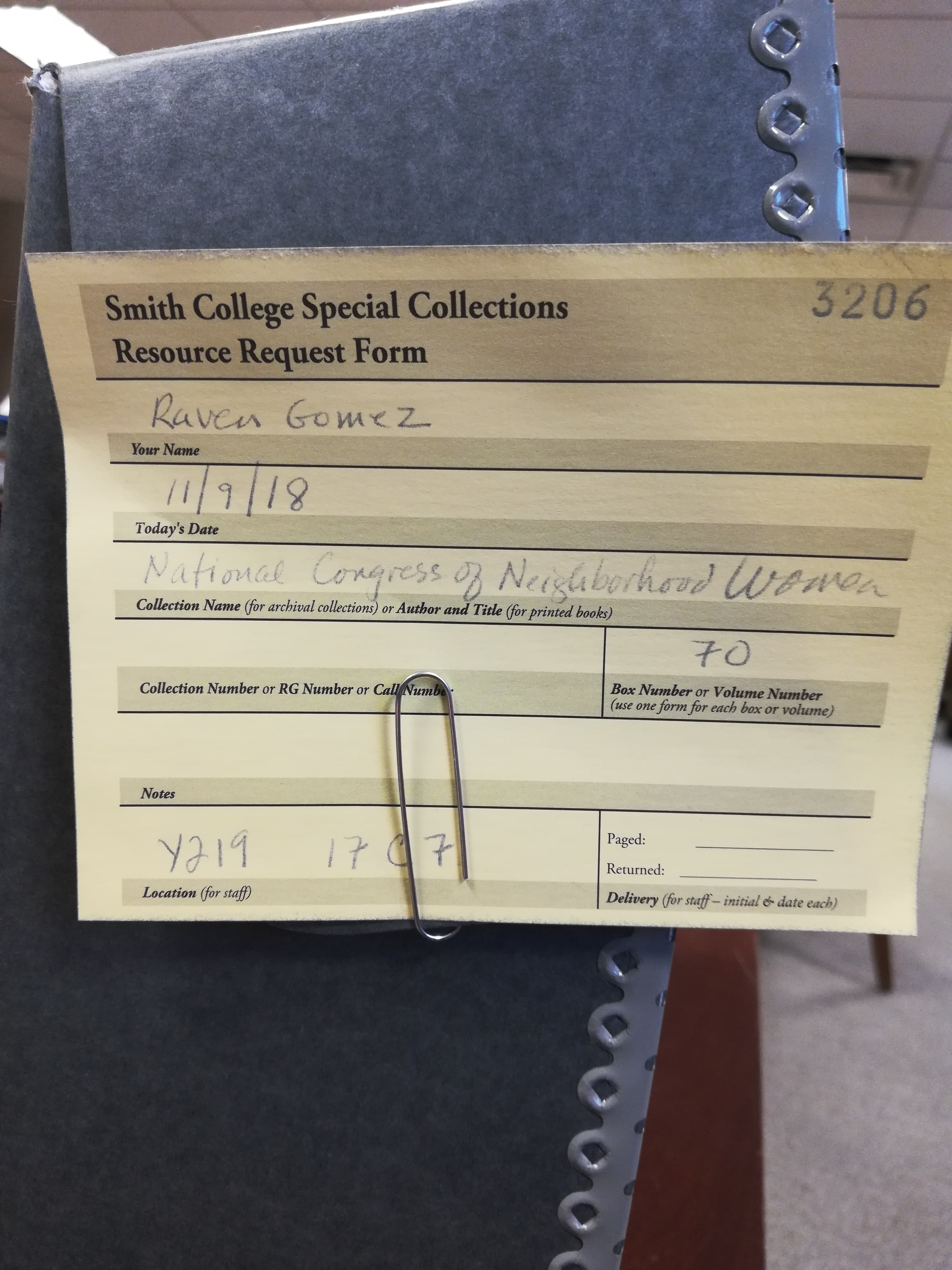

Apologies for the late blog post! I just returned from a weekend at my undergraduate institution, Smith College for an archives project deeply related to this week’s theme of DH and Archive studies.

Apologies for the late blog post! I just returned from a weekend at my undergraduate institution, Smith College for an archives project deeply related to this week’s theme of DH and Archive studies.